By Jade Boyd

Science Editor and Associate Director of News and Media Relations

Rice University Office of Public Affairs

Original Story

Feature Image: A prototype face shield produced as part of a joint effort by the Rice Center for Engineering Leadership and Rice’s Moody Center for the Arts. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Teams are donating, making, testing protective gear for health care workers

The growing crisis over COVID-19 protective gear hit home for Rob Raphael as he read the desperate Facebook messages from doctors trying to learn how to sterilize their own masks.

It was mid-March, and Raphael, a Rice bioengineering professor, had been invited to the online forum by a former student who’s now an anesthesiologist. The messages were eye-opening and gut-wrenching. Some hospitals were issuing doctors one mask per week. At many hospitals, doctors needing to sterilize their masks were on their own.

“It was an information source from the front lines, so to speak,” Raphael said. “That’s when I started shifting towards, ‘As engineers, what can we do to help?’”

Raphael and many more at Rice have helped. He has contacted hospitals to advocate for sterilization, and he’s researching ways to test sterilized masks. Others have responded by collecting or making gear or by improving gear that’s already in use.

Bring on the supply chain

What began as a 3D printing effort initiated by Fred Higgs, faculty director of the Rice Center for Engineering Leadership (RCEL), has gathered tremendous momentum and is scaling up with the goal of producing up to 600,000 face shields.

Face shields are transparent screens that cover the entire face and supplement protection provided by masks. While some types of face shields are disposable, others can be disinfected and reused many times. They are an important second layer of personal protective equipment (PPE) for front-line medical staff treating COVID-19 patients.

A project begun by Fred Higgs, faculty director of the Rice Center for Engineering Leadership, could wind up producing hundreds of thousands of face shields. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Higgs, the John and Ann Doerr Professor of Mechanical Engineering and vice provost for academic affairs, said “back-of-envelope calculations made by graduate students from my research lab” clearly showed that “PPE shortages in Houston would not be solved by 3D printing alone.” A technology supply chain had to be created.

Ebony Wiley, head of RCEL’s leadership initiatives, formulated a strategy to connect with potential customers, assess needs and engage with local suppliers and manufacturers. Kaz Karwowski, RCEL executive director, is leading supply chain development, and George Webb, RCEL industry liaison, is heading up customer relations. Cortlan Wickliff, associate vice provost for academic affairs and strategic initiatives, is assisting with compliance, legal and other issues.

Project subteams are comprised of undergraduate engineering students, all but one of whom are from RCEL. The technology subteam is headed by Eleazar Marquez, assistant teaching professor of mechanical engineering, and includes faculty from the departments of mechanical engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and bioengineering.

RCEL has already sourced and delivered 500 face shields to Harris County Public Health. RCEL also has partnered with the Moody Center for the Arts, and Moody Makerspace Director Rob Purvis has created 30 prototype face shields that can be given to Texas Medical Center hospitals and institutions for review and feedback. (For more about Purvis’ efforts to help with protective gear, check out this Rice News feature.)

Gathering and donating

Graduate students Yuren Feng (left) and Xiaochuan Huang with boxes of masks, gloves and other protective gear and lab testing supplies that Rice laboratories donated to the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston April 1. Another volunteer, graduate student Ruikun Xin, is not shown due to social distancing guidelines. (Photo by Qilin Li/Rice University)

Qilin Li, a professor in civil and environmental engineering, began collecting masks, gloves and other personal protective equipment (PPE) as soon as the university began ramping down on-campus research to promote social distancing.

“We reached out to all departments with wet chemistry labs to see what PPEs could be spared,” Li said. “We received a lot of responses within a very short time, and UTHealth received the first batch of donated items April 1.”

The first donation included 450 boxes of nitrile gloves, 700 masks, 294 disposable lab coats and approximately 100 shoe covers and 100 head covers, as well as COVID-19 testing supplies like pipette tips, microtubes and autoclave tape.

More has been gathered since then, and the efforts are ongoing. Donations from on- and off-campus sources are rolling in, and anyone who wants to donate can use this online form.

Organizing and advocating

When Rebecca Richards-Kortum and Jerzy Szablowski convened the Department of Bioengineering’s COVID-19 working group, “PPE” was one of the first channels added to the group’s Slack page. Within a few days of the March 23 resumption of spring classes, several departmental initiatives were underway.

“I realized we needed to organize all this stuff, and I’m on sabbatical and had more time, so I played a role in trying to connect researchers on campus and clinicians who weren’t connected,” Raphael said.

Raphael credited Szablowski’s initiative in organizing the department’s response, which includes critical care improvement and diagnostic, vaccine and therapeutic research and development.

After Raphael saw the desperate messages from doctors online, he spent hours reading about sterilization methods, procedures and testing. Then he started contacting hospitals to advocate for appropriate methods and policies.

He also began interacting with Dr. Sahil Kapur, a plastic surgeon at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, on new methods to evaluate the structural integrity of masks that had been sterilized. Evaluating how many times masks can be sterilized and safely reused is a major barrier for many hospitals, Raphael said.

“People publish average failure rates, but ultimately we would like a quick way to know that an individual mask has not degraded,” he said. Using equipment from his lab, he’s begun experiments to investigate if optical methods might be used for that purpose.

“The ultimate vision would be to have something akin to an assembly line, where you could make an optical measurement on sterilized masks and say, ‘Yeah, this one’s still good. This one’s still good. That one’s degraded.’

“I have no idea if we can do that yet, or how easy it would be to implement, but we’re working on a proof of principle,” Raphael said.

Better fit, better protection

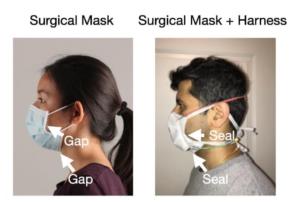

Researchers from Rice and MD Anderson Cancer Center have begun testing prototypes of a silicone rubber harness that will fit over a surgical mask and seal it to the face. (Image courtesy of J. Robinson/Rice University)

The masks that provide the greatest protection against inhaled viral particles are N95 respirators. These seal tightly, cover the mouth and nose, and have filters that purify air before it is inhaled. There are critical shortages of N95s the world over, and Kapur is also collaborating with two professors in Electrical and Computer Engineering, Caleb Kemere and Jacob Robinson, to create a silicone rubber harness that will fit over a surgical mask and seal it to the face.

“A big reason why surgical masks are not effective in protecting against aerosolized threats is because they allow unfiltered air to enter around the sides, bottom and top,” Kemere said. “Poorly fitted N95s suffer the same problem, which is why health care professionals are required to go through a special process of mask fitting and testing.

“Our hope is that if we can solve the leakage problem, then perhaps surgical masks can begin to be manufactured with materials of equivalent filtering ability as N95s, resulting in a simpler, easier, safer process for everyone,” he said.

Kemere has finished several prototypes and testing is underway in his neuroengineering lab at Rice’s BioScience Research Collaborative. Further tests are needed, Robinson said, but the simplicity of the design and the materials should help streamline production and regulatory approval. Kemere and Robinson hope to start providing harnesses to hospitals soon.

“With a single laser cutter and injection molding machine, we believe we can make several hundred harnesses per day out of materials that can be sterilized and reused and are compatible with federally approved surgical masks,” Robinson said.